论文链接:https://aclanthology.org/2022.findings-acl.109.pdf

论文代码:https://github.com/albertwy/SWRM

作者:吴洋、赵妍妍、杨浩、陈嵩、秦兵、曹晓欢、赵文婷

单位:哈尔滨工业大学、招商银行

1. 动机介绍

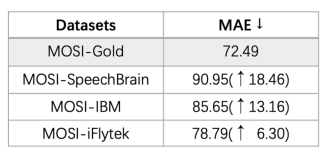

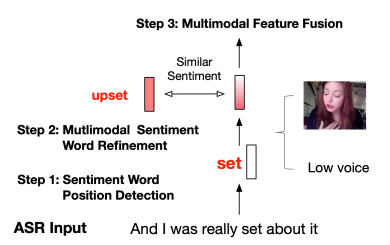

目前的多模态情感分析模型在真实环境下的模型性能产生大幅下降(见图1)。经过初步分析,我们发现以往多模态情感分析模型所使用的文本为人工标注的文本,而真实环境下,多模态情感分析模型只能利用自动语音识别模型的结果。由于自动语音识别模型(ASR)的模型性能限制,识别出来的结果往往带有噪音。通过进一步分析,我们发现在一部分数据中,自动语音识别模型把其中的情感词识别成了别的词语,进而导致文本的情感语义发生了变化(见图2)。针对这一问题(情感词替换错误),我们提出基于情感词感知的多模态词修正模型(SWRM)。该模型可以通过利用多模态情感信息来动态地补全受损的情感语义(见图3)。具体来说,我们首先利用情感词位置预测模块,找到可能是情感词的位置。其次,我们利用多模态词修正模块来动态地补全该位置词表示中的情感语义。最后,我们将修正好的情感词表示与图像/声音特征送入多模态融合模块来预测情感标签。

图1. SOTA模型(Self-MM)在理想环境(MOSI-Gold)和真实环境(MOSI-SpeechBrain/IBM/iFlytek)下的性能。SpeechBrain,IBM,iFlytek是我们所使用的ASR API。

图2. 情感词替换错误及其在三个真实环境数据集下所出现的比例

图3. 我们提出的解决方案

2. 模型方法

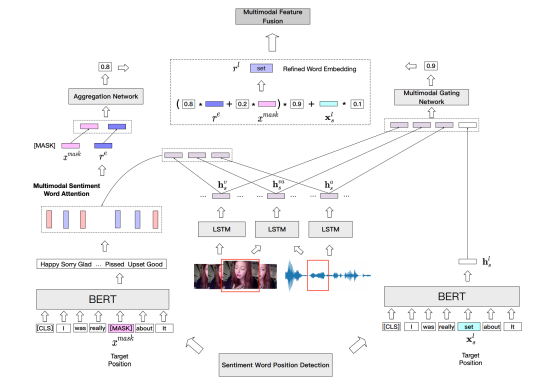

我们提出的SWRM模型共包含三个模块:情感词位置预测模块、多模态词修正模块和多模态特征融合模块。

2.1 情感词位置预测模块

情感词位置预测模块的核心思想是找出情感词在ASR文本中的可能位置。 由于ASR 模型可能将情感词识别为中性词,因此我们没有基于ASR文本中每个词的语义来判断该词是否为情感词。例如,给定一个正确文本“And I was really upset about i”, 而ASR 模型识别的结果为“And I was really set about i”。 模型会很容易将“set”这个词标记为中性词。因此,我们选择让模型找到可能是情感词的位置,比如预测出来“set”所在位置可能是情感词出现的位置。

具体来说,我们使用语言模型通过捕捉句法和语义信息来判断最有可能是情感词的位置。预测流程如下。首先我们使用[MASK]标记替换ASR文本中第i个词,然后将得到文本送入BERT中得到BERT在第i个词预测出来的k个候选词。接着,利用情感词典过滤出候选词中的情感词并将其个数记为ki。最后我们可以得到最有可能的位置的索引s。nl是ASR文本的长度。考虑到某些样本中没有情感词,我们利用阈值来进行筛选,如果ki>k/2,则p为1,否则为0.

![]()

图4. SWRM模型架构

2.2 多模态词修正模块

为了减少 ASR 错误的负面影响,我们提出了多模态情感词修正模块。

在该模块中,我们从两个方面来优化情感词的词表示。一是我们使用多模态门控网络从输入中过滤掉无用的信息词。 另一种是我们设计

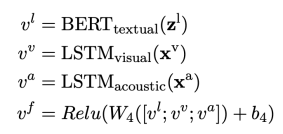

多模态情感注意力网络,用于融合BERT模型生成的候选词的有用信息。首先我们分别利用BERT和LSTM对文本特征,视觉特征,音频特征,视觉-音频特征进行建模。

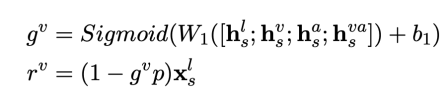

然后,利用多模态门控网络过滤情感词所在位置的表示的信息。

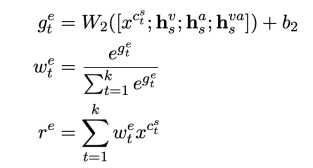

进一步,利用多模态情感注意力网络融合候选词中的有用信息。

由于我们想要的情感词可能未被包含在候选词列表中,我们在修正词表示时候还引入了[MASK]的表示。

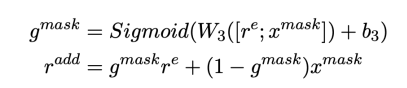

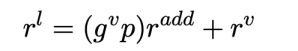

最后,我们将以上表示合并起来得到修正后的词向量。

2.3 多模态特征融合模块

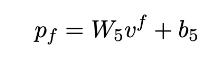

我们利用现有主流的方法来对修正后的词表示,图像特征和音频特征进行建模和融合。

最后利用一层线性层进行情感预测。为了和之前的SOTA模型Self-MM进行公平比较,我们也利用其采取的单模态标签生成和利用方法增强模型性能。

3. 实验

3.1 数据集

我们在理想环境下的公开数据集MOSI和我们构建真实环境下的数据集MOSI-SpeechBrain,MOSI-IBM和MOSI-iFlytek。相关数据集可以通过访问https://github.com/albertwy/SWRM来获取。

3.2 实验对比

表1. 真实环境下模型性能对比

表1的实验结果表明,我们提出的模型在三个数据集上取得了最优的性能。

3.3 消融实验

表2. MOSI-IBM数据集上的消融实验结果

表2展示了消融不同模块的实验结果。我们分别消融了情感词位置预测模块,多模态情感注意力网络和多模态词修正模块中的图像和音频信息。

3.4 样例分析

图5. 样例分析

从图5中我们可以看到,SWRM模型可以检测到输入ASR文本中情感词所在的位置,并且通过利用多模态信息对识别错的情感词进行优化,最后预测出正确的结果。

4. 结论

在本文中,我们观察到在真实环境中多模态情感分析的SOTA 模型的性能出现了明显下降,通过深入分析,我们发现情感词替换错误是导致性能下降的一个重要的因素。 为了解决这个问题,我们提出了情感词感知多模态词修正模型,该模型可以动态地优化词表示并通过结合多模态情感信息来重构受损的情感语义。 我们在 MOSI-SpeechBrain、MOSI-IBM 和 MOSI-iFlytek 上进行了实验,结果证明了我们方法的有效性。 对于未来的工作,我们计划探索利用多模态信息来进行情感词的位置预测。

► 参考文献 [1] D. Kahneman, Thinking, fast and slow. Macmillan, 2011. [2] K. Diehl, A. C. Morales, G. J. Fitzsimons, and D. Simester, “Shopping interdependencies: How emotions affect consumer search and shopping behavior,” 2011. [Online]. Available: https://msbfile03.usc.edu/digitalmeasures/kdiehl/intellcont/Shopping%20Interdependencies%20WP-1.pdf [3] T. A. Dingus, F. Guo, S. Lee, J. F. Antin, M. Perez, M. Buchanan - King, and J. Hankey, “Driver crash risk factors and prevalence evaluation using naturalistic driving data,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 113, no. 10, pp. 2636–2641, 2016. [4] K. Trezise, A. Bourgeois, and C. Luck, “Emotions in classrooms: The need to understand how emotions affect learning and education,” NPJ Science of Learning, 2017. [5] M. Minsky, The Society of mind. Simon and Schuster, 1986. [6] D. Schuller and B. W. Schuller, “The age of artificial emotional intelligence,” Computer, vol. 51, no. 9, pp. 38–46, 2018. [7] M. Soleymani, D. Garcia, B. Jou, B. Schuller, S.-F. Chang, and M. Pantic, “A survey of multimodal sentiment analysis,” Image and Vision Computing, vol. 65, pp. 3–14, 2017. [8] J. Wagner, E. Andre, F. Lingenfelser, and J. Kim, “Exploring fusion methods for multimodal emotion recognition with missing data,” IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing, vol. 2, no. 4, pp. 206–218, 2011. [9] S. K. D’mello and J. Kory, “A review and meta-analysis of multimodal affect detection systems,” ACM Computing Surveys, vol. 47, no. 3, p. 43, 2015. [10] D. Ramachandram and G. W. Taylor, “Deep multimodal learning: A survey on recent advances and trends,” IEEE Signal Processing Magazine, vol. 34, no. 6, pp. 96–108, 2017. [11] S. K. D’Mello, N. Bosch, and H. Chen, “Multimodal-multisensor affect detection,” in The Handbook of Multimodal-Multisensor Interfaces: Signal Processing, Architectures, and Detection of Emotion and Cognition-Volume 2, 2018, pp. 167–202. [12] T. Baltrušaitis, C. Ahuja, and L.-P. Morency, “Multimodal machine learning: A survey and taxonomy,” IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, vol. 41, no. 2, pp. 423–443, 2019. [13] S. Zhao, X. Yao, J. Yang, G. Jia, G. Ding, T.-S. Chua, B. W. Schuller, and K. Keutzer, “Affective image content analysis: Two decades review and new perspectives,” IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, 2021. [14] M. D. Munezero, C. S. Montero, E. Sutinen, and J. Pajunen, “Are they different? affect, feeling, emotion, sentiment, and opinion detection in text,” IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 101–111, 2014. [15] Z. Zeng, M. Pantic, G. I. Roisman, and T. S. Huang, “A survey of affect recognition methods: Audio, visual, and spontaneous expressions,” IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, vol. 31, no. 1, pp. 39–58, 2009. [16] F. M. Marchak, “Detecting false intent using eye blink measures,” Frontiers in psychology, vol. 4, p. 736, 2013. [17] Z. Zhang, N. Cummins, and B. Schuller, “Advanced data exploitation in speech analysis: An overview,” IEEE Signal Processing Magazine, vol. 34, no. 4, pp. 107–129, 2017. [18] M. B. Akçay and K. Oğuz, “Speech emotion recognition: Emotional models, databases, features, preprocessing methods, supporting modalities, and classifiers,” Speech Communication, vol. 116, pp. 56–76, 2020. [19] H. K. Meeren, C. C. van Heijnsbergen, and B. de Gelder, “Rapid perceptual integration of facial expression and emotional body language,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 102, no. 45, pp. 16 518–16 523, 2005. [20] R. Subramanian, J. Wache, M. K. Abadi, R. L. Vieriu, S. Winkler, and N. Sebe, “Ascertain: Emotion and personality recognition using commercial sensors,” IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 147–160, 2018. [21] A. Giachanou and F. Crestani, “Like it or not: A survey of twitter sentiment analysis methods,” ACM Computing Surveys, vol. 49, no. 2, pp. 1–41, 2016. [22] W. Rahman, M. K. Hasan, S. Lee, A. Zadeh, C. Mao, L.-P. Morency, and E. Hoque, “Integrating multimodal information in large pretrained transformers,” in Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 2020, pp. 2359–2369. [23] P. Chakravorty, “What is a signal?[lecture notes],” IEEE Signal Processing Magazine, vol. 35, no. 5, pp. 175–177, 2018. [24] D. Joshi, R. Datta, E. Fedorovskaya, Q.-T. Luong, J. Z. Wang, J. Li, and J. Luo, “Aesthetics and emotions in images,” IEEE Signal Processing Magazine, vol. 28, no. 5, pp. 94–115, 2011. [25] S. Wang and Q. Ji, “Video affective content analysis: a survey of state-of-the-art methods,” IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing, vol. 6, no. 4, pp. 410–430, 2015. [26] J. Yang, M. Sun, and S. Xiaoxiao, “Learning visual sentiment distributions via augmented conditional probability neural network,” in AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2017, pp. 224–230. [27] S. Zhao, H. Yao, Y. Gao, R. Ji, and G. Ding, “Continuous probability distribution prediction of image emotions via multi-task shared sparse regression,” IEEE Transactions on Multimedia, vol. 19, no. 3, pp. 632–645, 2017. [28] D. She, J. Yang, M.-M. Cheng, Y.-K. Lai, P. L. Rosin, and L. Wang, “Wscnet: Weakly supervised coupled networks for visual sentiment classification and detection,” IEEE Transactions on Multimedia, vol. 22, no. 5, pp. 1358–1371, 2020. [29] S. Zhao, X. Yue, S. Zhang, B. Li, H. Zhao, B. Wu, R. Krishna, J. E. Gonzalez, A. L. Sangiovanni-Vincentelli, S. A. Seshia et al., “A review of single-source deep unsupervised visual domain adaptation,” IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems, 2020. [30] U. Bhattacharya, T. Mittal, R. Chandra, T. Randhavane, A. Bera, and D. Manocha, “Step: Spatial temporal graph convolutional networks for emotion perception from gaits.” in AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2020, pp. 1342–1350. [31] Y.-J. Liu, M. Yu, G. Zhao, J. Song, Y. Ge, and Y. Shi, “Real-time movie-induced discrete emotion recognition from eeg signals,” IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing, vol. 9, no. 4, pp. 550–562, 2018. [32] A. Hu and S. Flaxman, “Multimodal sentiment analysis to explore the structure of emotions,” in ACM International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, 2018, pp. 350–358. [33] S. E. Kahou, V. Michalski, K. Konda, R. Memisevic, and C. Pal, “Recurrent neural networks for emotion recognition in video,” in ACM International Conference on Multimodal Interaction, 2015, pp. 467–474. [34] A. Zadeh, P. P. Liang, S. Poria, P. Vij, E. Cambria, and L.-P. Morency, “Multi-attention recurrent network for human communication comprehension,” in AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2018. [35] R. Ji, F. Chen, L. Cao, and Y. Gao, “Cross-modality microblog sentiment prediction via bi-layer multimodal hypergraph learning,” IEEE Transactions on Multimedia, vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 1062–1075, 2019. [36] H. Lyu, L. Chen, Y. Wang, and J. Luo, “Sense and sensibility: Characterizing social media users regarding the use of controversial terms for covid-19,” IEEE Transactions on Big Data, 2020. [37] R. Wu and C. L. Wang, “The asymmetric impact of other-blame regret versus self-blame regret on negative word of mouth: Empirical evidence from china,” European Journal of Marketing, vol. 51, no. 11/12, pp. 1799–1816, 2017.